Reptile Keeping: A Brief Introduction to Animal Welfare

I See far too many examples of reptile keepers using the term animal welfare as if it is a subjective descriptive word much like “quality of life”, rather than what it is. A field of science.

It gets thrown around as a buzzword perpetuating the misunderstanding about what it is. So we are now detailing animal welfare to help keepers truly understand what animal welfare is.

What is Animal Welfare?

There are many definitions of animal’s welfare, all roughly cover the same principles. I implore the reader to investigate animal welfare at a much greater detail than what is contained within this document. This serves only to ignite the spark in the modern keeper to introduce animal welfare science into their

philosophy and husbandry.

My personal favourite definition comes from the AZA Animal Welfare Committee (2012), it describes animal welfare as the following:

“An animals collective physical, mental and emotional states over a period of time, and is measured from a continuum from good to poor.”

Figure 1. Animal welfare is measured on a continuum from good to poor.

Notice the term measured, animal welfare is a science, and thus requires data for people to make evidence-based husbandry decisions. Research and objective observations are used to measure the welfare of an individual at any time.

For example, see the following observation statements:

(A) The royal python expressed a greater count of species typical behaviours when climbing opportunities were made available. Climbing opportunities should be provided to maintain current levels of behaviours the snake appears to be motivated to perform.

(B) The royal is climbing a lot so clearly, she must like the feel of the branches.

Do you see the difference? One is objective and is measurable via a count of different behaviours and the other is a subjective and opinion based.

An animal typically experiences good welfare when it is:

• Physically healthy.

• Well nourished.

• Has the ability to develop and express species typical relationships, behaviours, and cognitive abilities.

• Lacks pain, fear, or distress.

Please note that this is measured on an individual basis, and an individual’s physical and psychological state may change throughout its life. Even if an animal has a safe enclosure, a proper diet and is free from disease it could still not be in the positive range on the animal welfare continuum. If for example, it is lacking opportunities for species appropriate behaviour or is experiencing fear or distress. We must make sure we are meeting all aspects of a species physical and psychological needs so that an individual can thrive.

Introducing Freedom Models

1965

In 1965, public concern over the factory farming methods with production animals was rising. As a result, the Brambell Committee was formed and set out the original Five Freedoms. Here are the Five Freedoms 1965:

The freedom to stand up

The freedom to lie down

The freedom to turn around

The freedom to groom themselves

The freedom to stretch their limb

1979

In 1979, the original Five Freedoms were amplified to better ensure animal welfare in Great Britain. Here are the improved five freedoms:

Freedom from hunger, thirst, and malnutrition: by ready access to fresh

water and a diet to maintain health and vigour.Freedom from discomfort: by providing a suitable environment including

shelter and a comfortable resting area.Freedom from pain, injury, and disease: by prevention or rapid diagnosis

and treatment.Freedom from fear and distress: by ensuring conditions that avoid mental

suffering.Freedom to express normal behaviour: by providing sufficient space,

proper facilities, and company of the animal’s own kind.

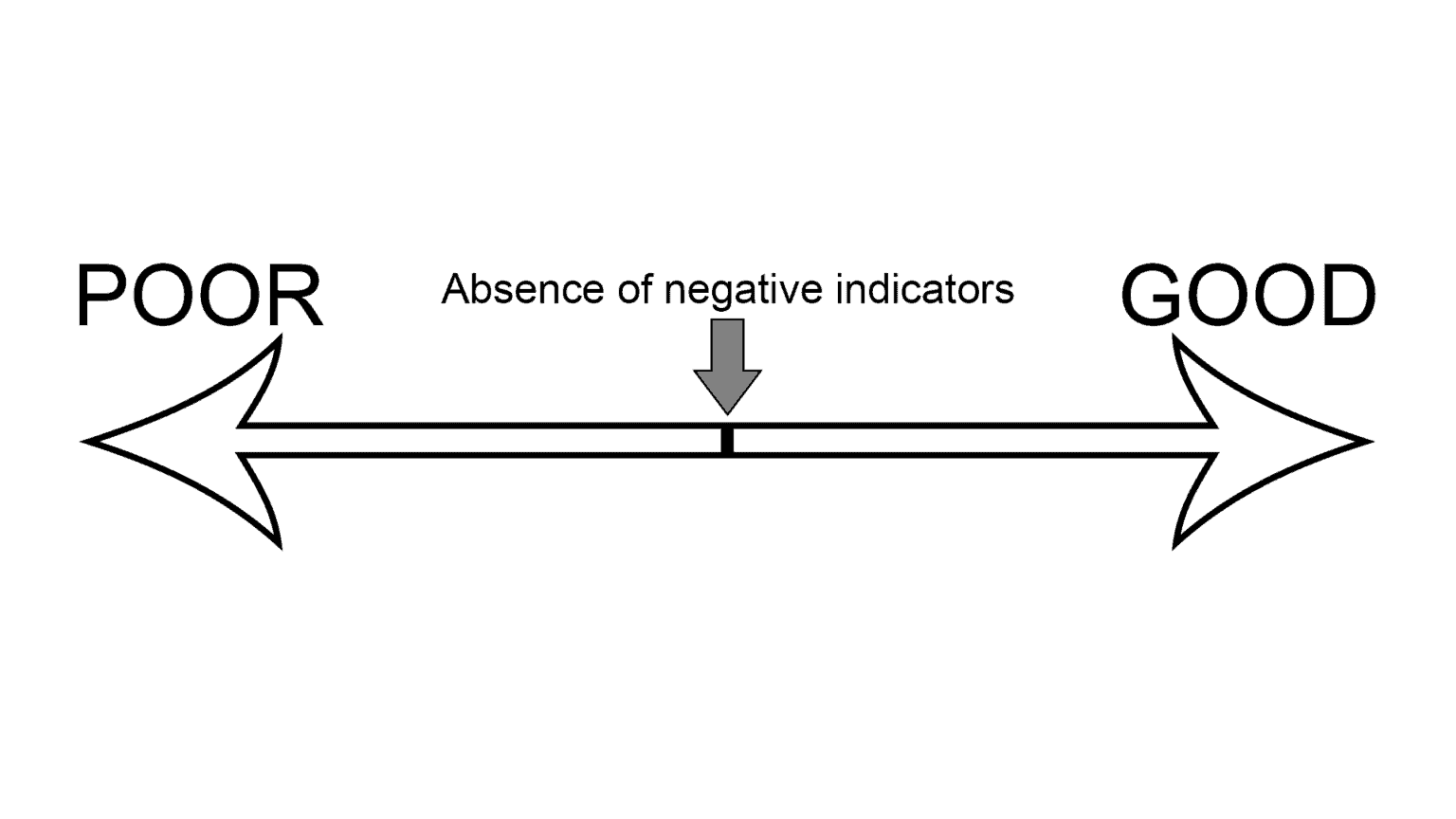

As you can tell historically when welfare was examined, measures of focus were typically negative and placed the avoidance of negative experiences as priority. While this is important, we were not also measuring positive indicators of welfare to determine where an animal falls along the continuum. In general, it is best practice to use a variety of measures that examine both positive and negative indicators of welfare.

Figure 2: Absence of negative Indicators may only equate to adequate welfare, but without

positive welfare indicators it is not necessarily considered good.

The absence of negative indicators of welfare does not equate to positive welfare. For example, a snake with a good body condition would be an indicator of physical well-being. However, if that snake was housed in a way that deprived that animal of behavioural diversity, then this would be a negative

indicator of mental wellbeing. Then this could not be considered positive welfare. Both physical and psychological factors make up the entire animal welfare continuum.

San Diego Zoo have an interesting take on animal welfare by looking at things in terms of inputs and outputs. An example of an input on the keeper’s behalf could be environmental size and complexity, and the output could be good muscle tone and species typical behaviours.

An example of potential negative input and output could be a barren environment with little complexity and the output would be low levels of behavioural diversity and lethargy.

It is important for the modern keeper to maintain an evidence-based approach to husbandry. Provide opportunities for reptiles to exert choice and control and opportunities for animals to engage in a diverse array of behaviour based on their natural history. Choice and control are important to make the behaviour of the animal meaningful. Providing a diverse number of opportunities for species appropriate behaviour helps ensure the animals can engage in the behaviours they are motivated to perform.

For example, a recent paper described python regius seeking out ultraviolet light and were observed basking for up to two hours per day in captivity. Based on this evidence the modern keeper should provide a UVB source with the opportunity for the snake to exert choice and control and move in and out of exposure at will. Allowing the snake to engage in behaviours they are motivated to perform is the input, and the greater behavioural diversity is the positive welfare indicator output.

Here is the study in question:

Hollandt, T., Baur, M., & Wöhr, A. C. (2021). Animal-appropriate housing of

ball pythons (Python regius)—Behavior-based evaluation of two types of

housing systems. Plos one, 16(5).

Let’s look at the five opportunities to thrive framework by San Diego:

Opportunity for a well-balanced diet: The provision of clean drinking

water and a suitable, species-specific diet will be provided in a way that

ensures full health and vigour, both behaviourally and physically.Opportunity to self-maintain: An appropriate environment including

shelter and species appropriate substrates that encourage opportunities to

self-maintain.Opportunity for optimal health: providing supportive environments

that increase the likelihood of healthy individuals as well as rapid

diagnosis and treatment of injury and disease.Opportunities to express species specific behaviour: the provision of

quality spaces and appropriate social groupings that encourage species

specific behaviours at natural frequencies and of appropriate diversity,

while meeting social and developmental needs of each species in the

collection.Opportunities for choice and control: providing conditions in which

animals can exercise control and make choices to avoid suffering and

distress and make behaviour meaningful.

Based on these principles I will demonstrate how this may translate to a reptile

species. If we take a 4ft corn snake as the example:

A variety of frozen thawed rodent species as well as avian species are

included in a varied diet, the way it is presented may vary from scent

trails to making the snake actively chase the rodent via feed tongs and

express constriction behaviour. Further including quail eggs to replicate

nest raiding behaviour at a raised height in the enclosure to encourage

physical activity and foraging.A variety of places of security are provided such as arboreal hides, cork

rounds, terrestrial logs, plants and leaflitter to allow the corn snake to

select the most comfortable secure place to perform a variety of

behaviours.Weekly weigh ins and visual health checks are carried out to monitor the

continuous condition of the snake, a variety of humid microclimates and

humid hides are provided to allow supportive environments when

shedding.The animal is provided with a 4x2x4ft enclosure to allow appropriate

quality space that allows both terrestrial and arboreal movement at natural

frequencies.Basking lamps and UVB is provided over a horizontal branch in the

enclosure with temperatures and light descending into a far corner to

allow the animal to move in and out of exposure exerting choice. A

warmed hide is offered on the terrestrial portion of the enclosure to

enable either thigmothermic or heliothermic thermoregulation.

Remember observing the animal and their responses to different situations can help ensure they are catered to at an individual basis. The modern reptile keeper should never assume that their animals are thriving, they should always think about new ways to improve the lives of the animals in their care. Just because a reptile has never shown higher levels of behavioural diversity, or health, it does not mean that it is not obtainable.

Figure 3: Example of how I set up my Mexican black kingsnake vivarium to offer choices.

One fallacy snake keepers fall into is presuming a snake does nothing but sit around all day, because in its rack with newspaper and a water bowl that’s all it does. Of course, it will have limited behavioural diversity because that environment is limiting. There are no inputs on the keeper’s part that allows those outputs.

What Is Stress?

Is all stress bad? Not all stress is bad, in fact some stress can be beneficial. For example, let’s say instead of tong feeding your snake its rodent, you instead drag the rodent across branches in the enclosure to make scent trails before leaving the item somewhere for the snake to find. This delayed gratification

results in heightened cognitive performance or may be psychologically rewarding as it follows scents to dead ends and is led astray before finally finding the food. Too little stress and a lack of challenges may result in a reduction in the animal’s welfare.

The key is to determine what types and levels of stress have detrimental or positive effects on the reptile’s welfare. While a certain circumstance might be considered stressful, some species might need to experience certain stressors as part of natural behaviour, an example of this is chasing as a part of snake courtship. We must understand that not all stress should be eliminated. And thus, we must determine good vs bad stress. Suffering can occur from stress when the stress is too severe or too prolonged, and the reptile cannot choose to remove itself or change the situation to relieve the stress.

Acute Stress

Acute stress is the reaction to an immediate threat. This threat may be real or merely perceived. After the threat is gone the physiological or behavioural changes in the animal that occurred as result of the stress, return to normal. However, several experiences of acute and severe stress that impact an animal in the short term can have long term negative effects.

Chronic Stress

Chronic stress results when a threat becomes prolonged, and the animal does not have the ability to change the situation to relieve the stress. This can have negative effects on the body. Long term effects of chronic stress may include suppressed immune response, abnormal behaviour, and lethargy.

An example of this would be a bearded dragon cohabited with a more dominant counterpart, an initial acute stressor may be the dominant social behaviour of the other dragon and the inability to remove itself from the environment may result in chronic stress.

Isn’t Animal Welfare Down to an Individual’s Ethics and Morals?

No, it is not, it is objective, and science based. While a person may believe strongly in animal welfare, welfare science remains independent.

Ethics is the standard of good or bad defined by societal or community standards.

Whereas morals are an individual’s standards of good or bad.

For example, in animal welfare science it is ethically considered wrong to purposefully induce negative welfare as a communal standard. Animal welfare and ethics or morals are separate, science is used in animal welfare to determine where an animal falls on the continuum from good to poor.

For example, live feeding a rodent to a snake may result in greater opportunity for the snake to express typical behaviours and show a positive welfare indicator, but at the expense of the rodent’s welfare, ethics and morals is deciding if the former outweighs the latter. If this scenario resulted in a 30% increase in behaviours from the snake, then ethics would be the societal subjective ethical decision to implement this or not, and some may agree or disagree.

For example, in the UK it is generally considered unethical to live feed vertebrates, but an individual may disagree and deem it acceptable, that is that individuals’ morals. But the increase in the behaviours is measurable science.

References

Melfi, V. A. (2009). There are big gaps in our knowledge, and thus approach, to

zoo animal welfare: a case for evidence‐based zoo animal management. Zoo

Biology: Published in affiliation with the American Zoo and Aquarium

Association, 28(6), 574-588.

Mellor, D. J. (2016). Moving beyond the “five freedoms” by updating the “five

provisions” and introducing aligned “animal welfare aims”. Animals, 6(10), 59.

Mellor, D. J. (2017). Operational details of the five domains model and its key

applications to the assessment and management of animal

welfare. Animals, 7(8), 60.

Miller, L. J., Vicino, G. A., Sheftel, J., & Lauderdale, L. K. (2020). Behavioral

diversity as a potential indicator of positive animal welfare. Animals, 10(7),

1211.

San Diego Zoo Academy animal welfare course (Hour long interactive

presentation): https://sdzwaacademy.org/courseAnimalWelfareGeneral.html